Why does a barbell not tip when it is faces unbalanced weights?

Consider a bench press. It has a free bar held up by two supports on each side of the bar. The supports are placed at equal lengths from their respective edges. The net weight of a free bar is 45 pounds. But, we can place a 45 pound plate on one side with nothing on the other side and the bar remains balanced without tipping. Why?

When there is no weight on the bar, the bar’s weight is distributed symmetrically about its midpoint and therefore its center of mass is at the center of the bar. This center is firmly between both the supports of the bar and so the bar does not tip. As long as the center of mass of the bar and weights added to it are within the supports of the bar, the bar will remain balanced.

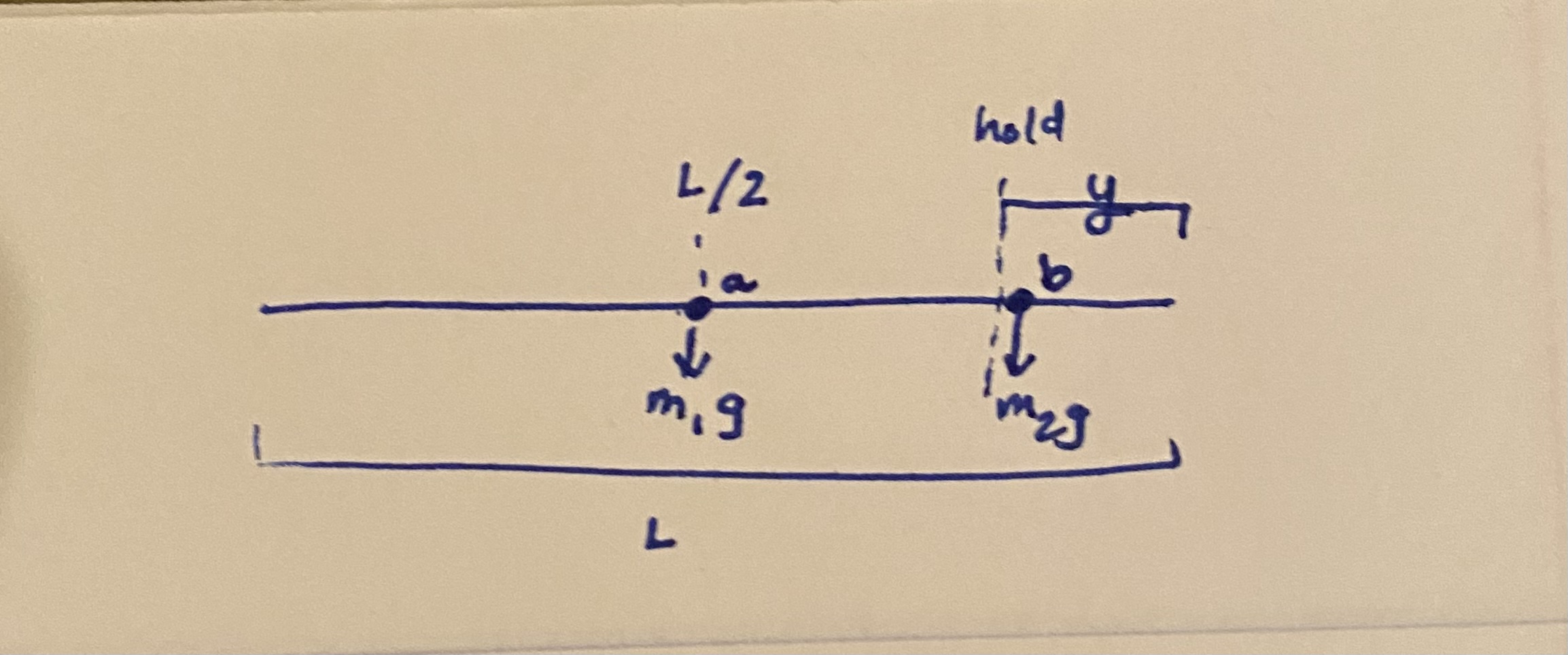

Let us consider what the system looks like when we place a weight on one end of the bar. This is a two object system: free bar and the weight. This is effectively a one-dimensional system so the location along the bar at which the torques are equal is where the center of mass resides. The force of gravity acting on each object happens at their respective center of masses. This is what a diagram of the relevant forces on the system looks like:

Note that the length of the entire bar is $L$, the point $a$ is the center of mass (COM) of the free bar acting at a position $\frac{L}{2}$, the point $b$ is at the COM of the weight added acting at a position $y$ from the end of the bar. The mass of the bar is $m_{1}$ and the mass of the weight is $m_2$. The supports are at a position $y$ and $L-y$ and we slide the weight as far in as possible which is effectively at $y$ since the weight’s mass is symmetric around its geometric center (since we assume the mass of the weight is distributed uniformly across its cylindrical volume).

Ok, so let $x$ be the COM of this two object system. It must be between $y$ and $L/2$. We know that $x$ must be chosen such that $(x)(m_2)(g) = (\frac{L}{2} - y - x)(m_1)(g)$. Solve for $x$. After doing the algebra, we end up with $x = \frac{(\frac{L}{2} - y)(m_1)}{m_1 + m_2}$.

Remember, the bar will not tip so long as $x$ lies on the closed interval $[y, L-y]$.

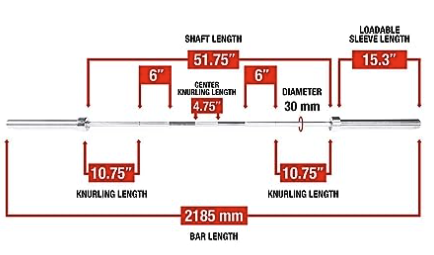

A traditional bench press bar is 85 inches long with the following structure:

The position of the holds is at 15.3 inches so $y$ is 15.3 inches, $L$ is 85 inches, and the weight of the bar is 45 pounds. Let us use metric definitions. 45 pounds is 20.4 kg, 15.3 inches is 0.388 meters, 85 inches is 2.159 meters.

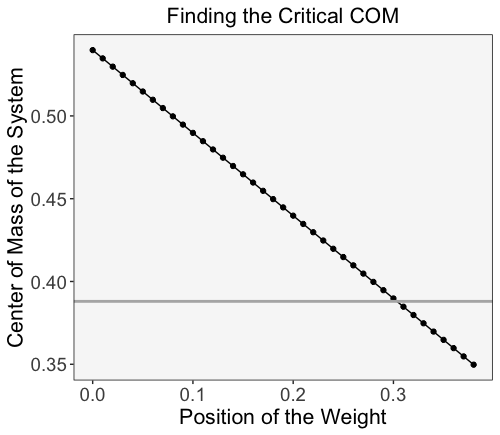

What happens as we place a 45 pound weight (20.4kg) at different locations on the loadable space? Let us graph $x(y)$ and find out. We restrict $y$ such that is must be between $[0, 0.388]$.

When the 45 pound plate is loaded between 0.304 m (11.96 in) from the edge to 0.388 m (15.3 in) from the edge, the system is stable. As a gut check, our analysis shows that a 45 pound plate pushed all the way in will keep the bar balanced, as we have observed experimentally. So, to make the 45 pound plate begin to tip the system, place the weight about 3.3 inches from the edge of the bar.

We can also ask what the maximum weight we can load onto one side of a bar such that it will not tip. This is straightforward given the framework we have put together above. Weights come in increments of 45 pound, 25 pound, 10 pound, 5 pound, and 2.5 pound plates. So, we can update the mass of the weight object with the combined mass of the plates we want to understand. We also need to updated $y$, the center of mass of the weight object since two plates no longer have a COM at the support. The updated COM of the weight object is at a location $p - z$ where $p$ is the location of the support (0.388 m or 15.3 in) and $z = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i = 1}^{n} z_i$ such that $z_i$ is the width of the i’th weight. We’ll save this computation for another time :)