Investigating the convergence in distribution of the sum of two dice rolls

“If the four didn’t roll as much as it did, I would have won”.

“The eight did not roll at all. If it rolled even a few times I would have won.”

We hear things like this all the time after a game of Catan. Traditionally, we expect that 7s are rolled twice as often as 4s because there are six different ways to roll a 7 but only three to roll a 4. This expectation is theoretical and true only in the limit after a very large number of rolls. At what number of rolls does the empirical distribution of the sum of two dice rolls converge to the theoretical distribution?

Most people implicitly assume that we can use this theoretical distribution in games like Catan to inform our decisions. In my experience, a Catan game with four players usually takes 60 to 90 rolls. How well does the empirical distribution of two-dice rolls match up to the theoretical in 60-90 roll scenarios? By trying to understand this we can judge to what extent basing our decisions on the theoretical distribution is appropriate.

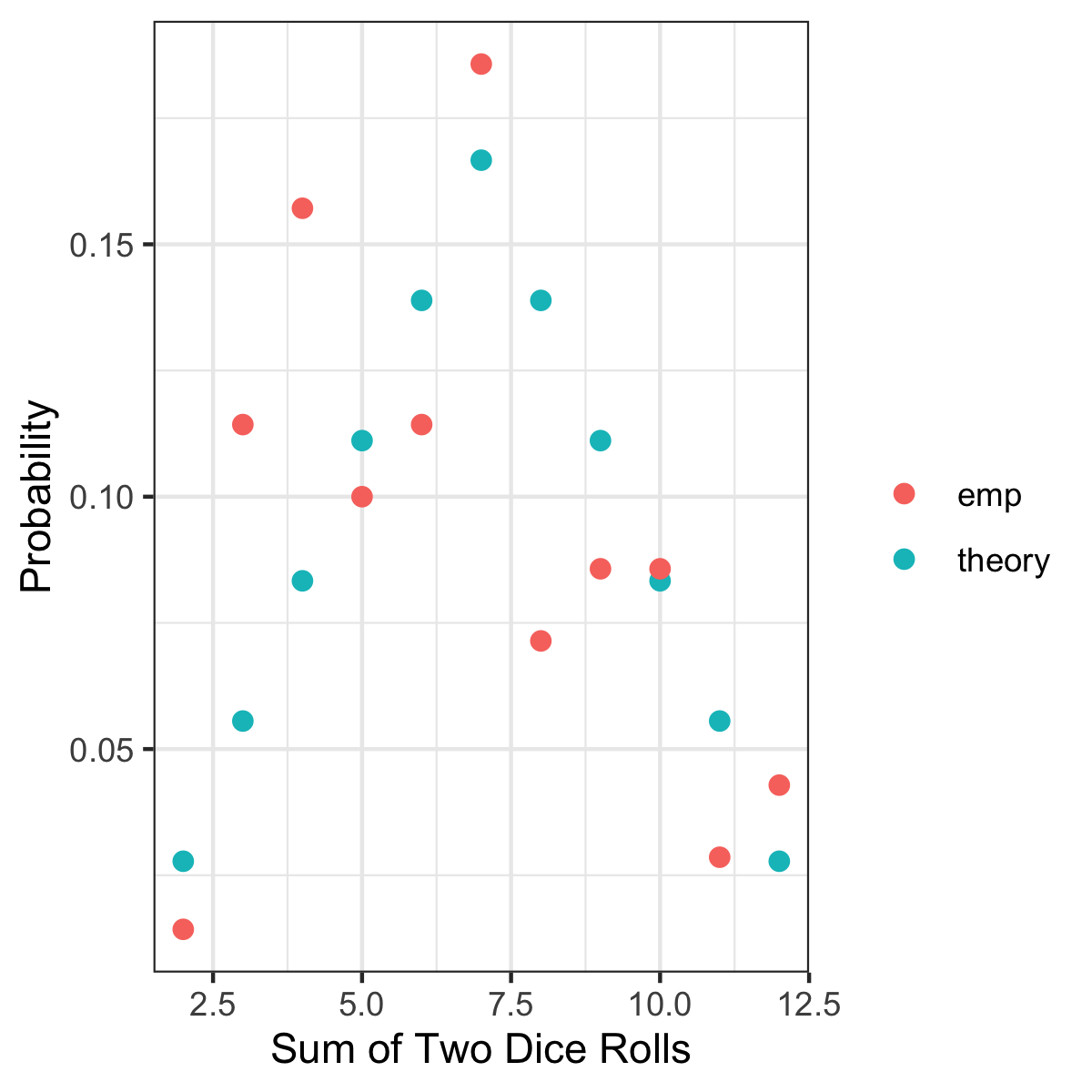

Here is one realization of the outcomes when two dice are rolled 70 times.

Notice that a 2 was not rolled in 70 tries. And, both 3s and 4s were overrepresented whereas 8s and 9s wereunderrepresented. There is marked deviation between the empirical (red) and theoretical (blue) frequencies.

The law of large numbers, LLN, (sample average approaches true mean) ~basically~ holds at 70 rolls. Simulating 100 70-roll games, the 95% empirical quantiles for the mean roll value is (6.48 to 7.47). The quantile symmetrically hovers around the true mean of 7. Though the LLN roughly holds at 70 rolls, it tells us only of the mean of the distirbution, not the shape of the actual distribution - which is what we care most about when making decisions in Catan.

Now, the most important question with respect to Catan and other two dice based board games is at what number of rolls does the empirical distribution of dice outcomes effectively resemble the theoretical distribution.

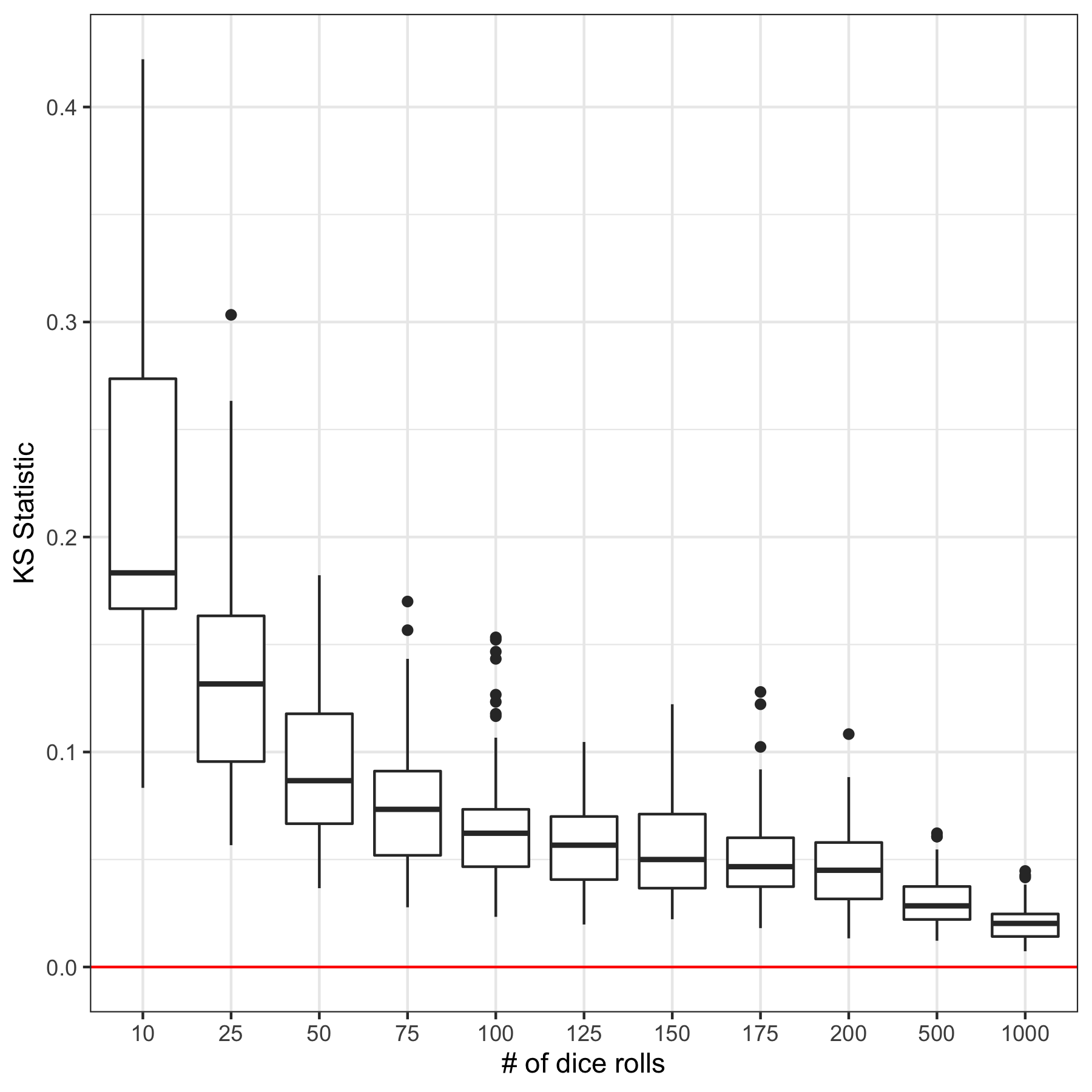

We can assess this convergence. First, we simulate an n-roll game and note the empirical probabilities. We can measure the deviation of this realization to the theoretical probabilities by looking at the largest absolute difference between the two cumulative distribution functions, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) statistic. The larger the KS value, the more deviant the empirical dice sums are from the theoretical. Doing this across for many n-roll games, repeating it 100 times at each n, we observe:

The KS statistic decreases as the number of dice rolls increases, an expected result. Further, we observe that the variance (approximated by the height of the boxes in the boxplot) increases as the number of rolls decreases - another expected result. Between 100 and 200 roll games, there appears to be a plateau in convergence to the theoretical probabilities. For our purposes, 50 and 75 dice rolls produce distributions that are indeed quite variable and different from the theoretical levels.

So, what does this mean for Catan-like games? I would argue that less emphasis be placed on the theoretical probabilities. Take advantage of the increased variance in these games and play more freely. Place settlements on 4s, 5s, 9s, and 10s with more confidence.