Conducting N-of-1 Trials: A case study on how to find statin intolerant patients that are actually statin tolerant

Well-executed clinical trials provide physicians with solid data but take time, are costly to do, and sometimes their results cannot be generalized uniformly to the broader population.

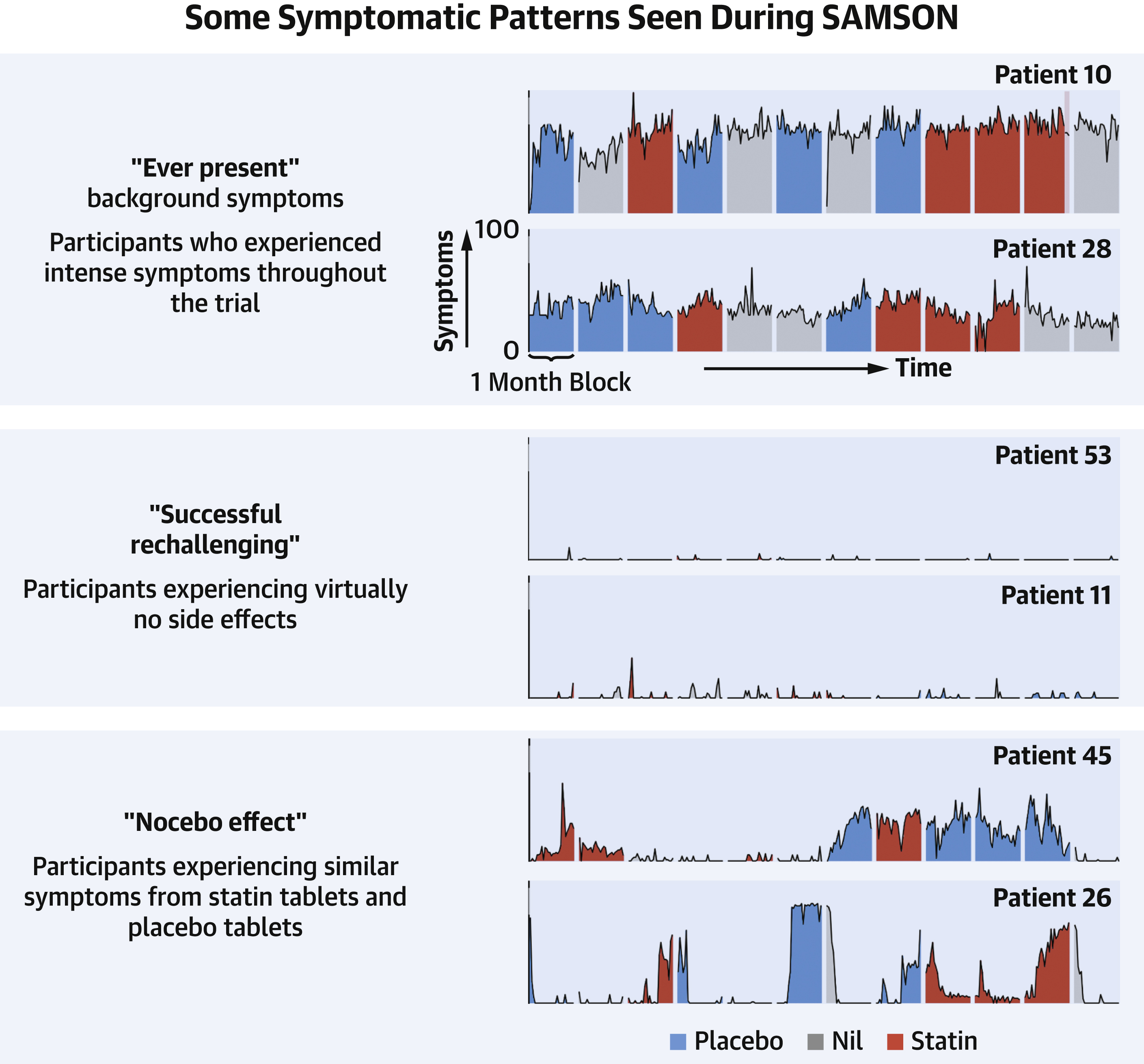

Let us explore this last point by looking at the SAMSON trial. Each patient was assigned to either placebo, statin, or no pill groups each month for 12 months; each patient was garaunteed 4 months of each group but their order was randomized. Blind to their treatment group during these 12 months, each patient reported a symptom intensity score from 0-100 each day. Only patients who were statin intolerant, either unwilling or unable to take statins, were enrolled in this trial. 49 patients successfully completed the 12 month trial. From Figure 2 in their paper, shown below, there are two subgroups of statin intolerant patients who should be given statins: a) the “successful rechallengers” that were able to tolerate statins with virtually no side effects; b) the “Nocebo effect” patients who experienced similar symptoms in placebo and statin months but not in empty months. The “Nocebo effect” subgroup should be given statins because it appears that the symptom scores are elevated whenever any pill is taken, even a placebo, and not related to the statin at all. As the SAMSON paper points out, it could be that the patient is more aware of their background bodily fluctuations or anticipating certain symptomologies because of the statin-based information to which they have been exposed.

Figure 2 from the 2021 SAMSON paper

SAMSON showed us that we should figure out which statin intolerant people belong to the Nocebo effect and successful rechallenger groups so that we can get them back on statins. Likewise, we should figure out who is certainly statin intolerant so that we can make a decision as to whether the statin side-effects are worth braving for the medical benefit statins provide relative to the risk-reward profiles of other LDL lowering medications out there (e.g., bempedoic acid, pcsk9 inhibitors).

Imagine a statin intolerant patient walks into your clinic. How do you figure out which group they belong to? Today, most clinicians do an informal experiment where they start and stop the statin for a period and ask the patient to report back. This is dangerous. As the SAMSON investigators write,

Prompt onset and offset of symptoms after starting and stopping tablets is often interpreted by patients and clinicians as evidence of causation. Our data indicate that this is true, but because the kinetics are identical between placebo tablets and statin tablets (Figures 3 and 4), the causation is from taking a tablet, rather than from the tablet being a statin. The danger of the informal experimentation that is currently recommended in North America (19), Europe (20), and the United Kingdom (21) is that even if there is a preplanned schedule and daily symptom scoring, without a placebo it is inevitable that nocebo symptoms will be misattributed to the statin. This phenomenon would unfortunately contribute to the 50% of statin starters who stop. Just as unfortunate current clinical practice might entrain a nocebo response, experience of multiple crossovers with no-tablet periods might be helpful to reverse the process, desensitizing patients to this nocebo effect

All three-arms (placebo, empty, and statin) are required to reach a conclusion for any individual patient. Essentially, we need to conduct an N-of-1 trial where we do all three arms for an individual patient and figure out which SAMSON subgroup they belong to. Do we need to do a 12 month period? Probably not. The longer the trial, the more data we collect, and the more sure we can be in our subgroup classification. That being said, two-thirds of the time in this trial, the patient is not on LDL modifying therapy placing them at an increased risk of a serious cardiac event. The duration of the N-of-1 trial should be tempered based on the level of cardiac event risk. Any number of risk calculators exist in the literature, with the most prevalent being the Framingham 10-year risk score.

How do we conduct this N-of-1 trial logistically? We need an app to measure their daily symptoms. Keeping in line with SAMSON, this app can simply ask the patient each day for a number between 0-100 of their overall symptom score. More complicated and granular measures of side-effects can be created, but for this use-case it seems unneccesary at the moment. Returning back to the logistics, in N-of-1 trials, we need pharmacies to dispense statin-look alike placebo pills such that the patient is blinded. Manufacturers ship their drugs to wholesalers who then ship to pharmacies. We need to create a company to manufacture these statin-like placebo pills in a GMP facility so that they can then be distributed to the wholesalers and subsequently the pharmacies where the patient can pick them up.

Now, we can run N-of-1 trials on statin intolerant patients and subtype patients successfully. By definition, statin intolerant patients are not on statins. So, getting some of these patients back on statins is both of medical benefit to them and economic benefit to the company that made the statin. As such, health insurance companies may be incentivized to pay for this sort of N-of-1 trial.

Before starting a N-of-1 trial placebo platform, we need to understand the market. Some things to understand include the total addressable population of statin intolerant patients, the all-in cost of conducting N-of-1 trials, and the savings of a statin intolerant patient being back on a statin. Further, it stands to reason that if we can make statin look alikes, we can also make look alikes of other medications. Now we can do N-of-1 trials involving a placebo arm for patients with other conditions too. To not do harm to patients, we need to be careful in choosing the right patient subpopulations and indications.

On a somewhat tangential note, this platform can also be used to conduct decentralized trials. The app-based tracking of user-reportable treatment endpoints and/or placebo delivery to pharmacies make it easier to recruit patients which may lower costs and should definetly increase accessibility to trials.